Roman god of wine and harvest inspired by the Greek Dionisius, symbol of controversial rituals celebrating pleasure and inebriation, naked yet crowned, not boy nor man, son of Jove, king of the gods who seduced a mortal woman, symbol of abundance, celebration and joy, but also of madness, ecstasy and depravity, sacred and profane, this is Bacchus.

This figure, full of contrasts, was represented by the young and controversial painter, Caravaggio, whose real name is believed to be Michelangelo Merisi, whose private life was full of promiscuity and scandal, who spent his later life fleeing a death sentence for murder, only to become one of the most celebrated Italian painters of all time.

The painting, Bacchus, was commissioned by his patron and protector at the time, Cardinal Del Monte, in 1595. It was commissioned as a gift for the Grand Duke of Florence, Ferdinando I dei Medici, to celebrate the wedding of the duke’s son, Cosimo II, and also to consolidate their lucrative friendship, not without irony considering that the Grand Duke himself was a teetotaler.

Caravaggio’s Bacchus was born in this climate of contrasts, ambiguity and irony in a masterpiece that strikes the senses and seems to immerge the spectator in a dilemma between what is sacred and what is profane.

Let us enter this dilemma and discover the allusions woven within it, and consequently within the story of wine.

With a dynamic play of light and shadow, Caravaggio’s paintings seem to spring out suddenly from the canvas, capturing the spontaneity of a moment with all the emotions and sensations involved. His realism is violently visceral in its suddenness found in expressions that deform the face, in ripe and succulent fruit that is starting to rot, and in gestures that are dramatic or tender, but never banal. They offer a vision of humanity which is raw, sometimes full of suffering, other times full of ecstasy, but above all fleeting, where life, intense in as much as it is delicate, is always framed by the nearness of death.

The impact of this realism goes beyond Christian iconography and symbolism, characteristic of the Baroque period, appealing directly to our senses with candid factuality tainted by ambiguity and irony. They seem to ask the spectator to react as if one were in that moment being depicted.

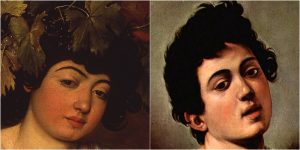

The moment which meets the spectator in Bacchus is that of an adolescent boy, nearly undressed and inclined, who is offering a glass of wine just poured. The bubbles floating in the carafe next to him and the ripples in the wine glass give the impression of realty, the impression that the spectator has just entered this intimate scenario with Bacchus.

The cinematic light illuminates this gesture while his body seems to be sinking back into the obscure shadows of the background. The hand offering the wine is trembling, yet the gaze is relaxed and languid with a playful glint. Maybe the boy is about to laugh, or perhaps he is intoxicated, or possibly insecure about what he is offering? Whatever it may be, his eyes immediately fix upon the spectator, almost as a sort of challenge, pulling one into the scene where ambiguities continue to reveal themselves.

The glass of wine is offered from the left hand, a detail which indicates the theory that the subject was painted as a self-portrait using a mirror, wherein it was actually the right hand, a much more comfortable position. This technique has been noted also in other paintings by Caravaggio.

However, the subject does not resemble Caravaggio but rather Mario Minniti, a young boy taken from the streets of Rome and an intimate of the painter. Minniti modelled for many other paintings including: Boy with a Basket of Fruit (1593), Cardsharps (1594) and Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1596).

A self-portrait can be found, instead, in the reflections of the carafe. It is small and subtle, almost not even there. Nonetheless, it is present, shattering any idea of intimacy the spectator may have had. In addition, the presence of the artist suggests the artificiality of the scene, no longer a spontaneous gesture but a choreographed one.

Gliding the eyes towards the center of the painting, one sees that the right hand is touching a black bow which is holding the sheet around the boy. Some claim that this is a symbol of the knot that unites God with man, and in fact there are religious readings of the painting.

Maurizio Calvesi, an Italian art historian and critic, speaks about a possible reference to the text Affetti della Mistica Theologia, written by Gregorio Comanini in 1590. A principal theme of the text is the union between God and man, explored in a spiritual reflection of Cantico dei Cantici, The Song of Songs also known as The Song of Solomon. Calvesi suggests that the interpretation of Jesus as a bunch of grapes, pressed and reborn as wine in the text could be read in the painting as an offering of the blood of Christ as a symbol of sacrifice and salvation.

The Song of Solomon is, in effect, a wedding verse, which is interpreted by Comanini as the loving desire of man to receive the blessed kiss of God, alluding to a symbolic wedding between God and his people. Considering that this painting was commissioned in honor of Cosimo II’s wedding, it’s a probable hypothesis. In any case, The Song of Solomon exists on the margins of religion as a sacred scripture that is erotic in tone.

In fact, some critics sustain that the effeminate and seductive adolescent boys, subjects in Caravaggio’s early paintings, would allude to a certain homoeroticism. Donald Posner was one of the first to publish a thorough analysis in Caravaggio’s Early Homoerotic Works, in which he refers to Bacchus as resembling a sort of geisha, offering maybe more than just a glass of wine, while loosening the bow holding his clothes on, asking the spectator to surrender to the delight of their senses.

From this point of view, the gesture of undoing the bow also undoes the illusion of divinity. No longer an immaculate offering from Bacchus, but a profane one, prohibited and outside the conventions and morality of the period it was painted in, in which there appears a conflict between spiritual transcendence and the fulfillment of physical pleasures.

The more the spectator descends in these ambiguities, the more the appearance of symbols dissolve. The irony in the painting persists in this play between contrasting elements, the divine veiled in profanity, the corrupted icon, the deceptive impressions, all directed towards the senses, both physical and emotive, of the spectator.

Through Caravaggio’s subject, subjectivity itself, encoded in representation, iconography and even morality, is revealed. Bacchus is positioned at the limits of clarity, where the concreteness of symbols rival perception, ambiguous in as much as it is subjective.

In this context, wine sustains the symbolism of the blood of Christ, but it also solicits to our inner desires, tempting to corrupt us, capable of provoking reverence or debauchery, sacred and profane and everything in between.

While there are many interpretations of the painting, I believe that the irony of Caravaggio’s Bacchus and its ambiguity gives light to the spectrum of perception, where the act of offering a glass of wine, of drinking a glass of wine, is an invitation to embrace the enigmatic quality of wine in itself.

Sources: Giulio Argan, Storia dell’arte italiana, vol. 3. Giovanni Baglione, Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti. Maurizio Calvesi, La realtà del Caravaggio. D. Posner, Caravaggio’s homoerotic early works, in ” Art Quarterly”. http://www.cultorweb.com, https://www.arteworld.it, https://www.artble.com, https://www.geometriefluide.com

Thank you for this beautiful article! I like the idea of wine as profane and sacred at the same time, a religious symbol as well as a representation of physical/worldy pleasure, spirit and body. It feels very much in line with the type of realism that Caravaggio represented. A realism that, however, does not deny mysticism and ambiguity, and this dubble nature is precisely its appeal. If you don´t know him already, you should read something by Armando Castagno (https://www.einprosit.org/guided-degustations/armando-castagno/), he is teaching the course “Art in wine making regions” at UNISG and is an amazing art historian as well as wine expert! The analogies that he manages to make between art and wine are truly fascinating. I don´t think our class was ever as quiet and concentrated as during his (3 hours long, without a break) lecture on Caravaggio,

Thank you for your comment! It certainly is an intriguing realism that seems to capture both the seen and unseen, tangible and allusive simultaneously. And it’s a credit to Caravaggio that this appeal has been sustained throughout so many generations. Thanks for the link, I’ll have a look!

Thank you for this beautiful article! I like the idea of the wine as profane and sacred at the same time , a religious symbol as well as a wordly/physical pleasure, spirit and body. It feels very much in line with the new type of realism that Caravaggio represented in his paintings. A realism which, however, does not not deny mystiscm and ambigiuty, and this dubble nature is precisely the appeal. If you don’t already know him, you should read something by Armando Castagno, (https://www.einprosit.org/guided-degustations/armando-castagno/), he is teaching the course “Art in wine making regions” at UNISG and is an excellent art historian as well as wine expert!! The analogies that he manages to make between art and wine are just astonishing. I don´t think our class was ever as silent and concentrated as during his (3 hour long, without a break) lecture on Caravaggio.

Hidden talents Danell, excellent article D, not that I understand everything but I recognise “quality” when I see it or read it. 👍🍷 B.